- Home

- Michael McKeown

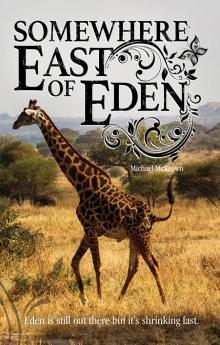

Somewhere East of Eden Page 2

Somewhere East of Eden Read online

Page 2

“So how was your day? Any luck with Mkubwa?” For a Scotsman, he had no trace of a Scottish accent.“Couldn’t have been better.” I told him about our encounter and my visit to Simon’s manyatta.

“Wonderful.” He signaled to the barman. “How about dinner – are you free this evening?” he asked as if we were in New York or London with any number of options open to me. “If you are, my girlfriend will be joining us if that’s alright.”

“Dinner with your girlfriend sounds delightful, “I said accepting an ice-cold Tusker beer.

At that moment, a slimly built woman in a powder blue T-shirt and cream linen trousers stood up and excused herself from a small group of Italian tourists and joined us. Her ash blonde hair was tied up in a single, silky plait and a silver bracelet circled one honey-coloured wrist.

“Sàra Ferenczy,” Ewan said by way of introduction.

“Ewan has been telling me about you,” she smiled. Her English was perfect with only the faintest trace of continental flavouring.

“Not all of it’s true,” I assured her.

“About the snake, you mean?” she smiled with well-feigned innocence.

I looked at Ewan reproachfully and gave Sàra a long-suffering smile. My encounter with a small green, and as it later turned out harmless, snake in the shower at Ewan’s former tented camp and subsequent precipitate dash into a dining room full of startled guests, was a moment I preferred to forget.

“It probably looked like a green mamba,” she said tactfully. “We had one that came into the vehicle maintenance yard last week and at first nobody took any great notice of it.”

“A green mamba. You mean they come into camp?” I felt a ripple of alarm.

“Not into the lodge itself. Well very rarely.” She turned to Ewan for confirmation. “When was the last time we saw one?”

Ewan considered. “Probably that one you found coiled up in the linen cupboard,” he reflected.

“And that was two or three months ago,” Sarah said with a confirmatory nod of her head.

“A green mamba in your linen cupboard?” My voice sounded disconcertingly like a squawk.

“I remember thinking how beautiful it looked, so sinuous and graceful,” Sàra continued as though recalling an encounter with a particularly handsome peacock or some brilliantly plumaged tropical island bird. I looked at her nonplussed. A green mamba possesses the most rapidly acting snake venom toxin known, resulting in dizziness, excruciating pain, convulsions and muscular paralysis leading to cardiac arrest, often within thirty minutes. The symptoms were all graphically described, together with luridly explicit images, in the various books I had read on African snakes, and yet all this girl could talk about was the mamba’s sinuous grace and how attractive it was. I sat down opposite her warily whilst Ewan called for more drinks.

Sàra, it turned out, was a wildlife biologist, currently working with a privately funded cheetah project set up to find a modus vivendi in the perennial conflict between cheetah and local people and their livestock. She had the light-blue eyes, high cheekbones and almost translucent complexion that corresponds to Hollywood’s concept of Nordic-Slavic beauty ever since Garbo lit up the screen as the doomed courtesan in Camille.

“It’s a battle for space, or rather the lack of it,” she said anticipating my question. “More than any other predator, cheetahs require vast expanses of land with water and prey to survive. Until twenty years ago they used to inhabit home ranges of up to 800 square kilometres Now, with loss of their habitat through human encroachment and land fragmentation that kind of space is going fast.”

“So, what are their chances?”

She allowed herself a small pause for deliberation. “In the shadowlands, if I’m being perfectly honest. There are so many imponderables. In Zimbabwe for example, their numbers have dropped from over twelve hundred to around one hundred and seventy in just twelve years.” She twirled the stem of her wine glass. “Ultimately it will depend on finding a way for them to share the land with people. In other words, avoiding conflict with cattle and other livestock.”

“Which won’t be easy.”

“At present. we are trying to establish the direction and frequency of their movements using GPS tracking collars. Once we know that we will try to pinpoint land features where they can move freely without encountering livestock.”

The co-operation of local communities was, I knew, a crucial piece of the jigsaw in the success of such projects and I asked her how the Samburu had reacted

“Very positively. Fortunately, they have a long tradition of co-existing with wildlife and so far, the response has been good. It’s a big issue obviously. Their livelihood revolves around their cattle.” She shrugged and took a sip of her wine. “It’s an encouraging start but there is still a long, long way to go.”

“Scientists are always cautious,” Ewan interjected as though explaining an unfortunate inherited defect. “I’ll make a bet with both of you now that cheetah will still be roaming here a hundred years’ from now.”

“And you’ll be there to collect your winnings?” Sàra said. She smiled at him and allowed the smile to linger

But the cheetahs’ problems it seemed did not end there. Equally as disturbing was the escalating trade in captured infant cheetahs as exotic pets in the Gulf States where they have become a status symbol, associated with glamour and prestige, featured in TV advertisements for Lamborghinis and paraded in the fashion industry. It was, Sara believed, a significant factor in the cheetahs’ decline.

At this point, a waiter arrived to say our table was ready and we followed him to the open-ended dining room with generously spaced-out, candlelit tables. Over sautéed garlic scallops and a delicious roast Molo lamb, Sàra gave me a rundown on the illegal cheetah cub trade. She spoke incisively and with insight about a pitiless business in which entire litters of cheetah cubs were seized from their mother at four to six weeks old and marketed through internet classifieds to the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia.

“It’s a horrific but lucrative trade and demand is growing through advertising on social media – mainly Instagram.” She shrugged ruefully. Most people simply have no idea that it’s happening.”

“And the buyers?”

“Uber rich yuppies. Young men prepared to pay upward of US $10,000, to drive with one as a front seat passenger in their latest Nissan SUV.

I asked her who did the trafficking.

“Organised criminal gangs. They smuggle them in small fishing boats across the Gulf of Aden and then by truck to the Gulf States. The conditions, as you can imagine, are appalling.”

“So many of them die in transit? Or am I jumping to conclusions?”

“Sadly, your conclusions are right. Well over eighty per cent.”She smiled disarmingly. “Do you think we might lighten up and change the conversation?”

I asked Ewan if he had learned any Hungarian, widely regarded as being the most difficult of European languages for an English-speaking person to learn, because of its grammar, spelling and pronounciation.

“You try it,” he laughed shaking his head. “All those S’s and Z’s and that’s before you come to all the ts’s and dx’s.

“Like Czardas?” Sàra arched a quizzical eyebrow at him, stressing the a in the first and second syllable. “Remember how you insisted in joining in?” They exchanged smiles and she turned to me. “We attended my sister’s wedding party in Budapest and as the evening wore on things got a bit wild. Ewan insisted on dancing a czardas.” I looked at him impressed. The wild, passionate, whirling Hungarian folk dance, in which the woman is lifted high in the air by her partner’s outstretched arms, demanded a brio and stamina that I knew to be well beyond my feeble limits.

I complemented her on her own faultless Englis

“We learn it from an early age at school along with French. Perhaps French less now which I think is a shame. I mean who wouldn’t want to read Flaubert or Colette in the original. It’s such a beautiful language.”

> Over dessert, talk veered to Budapest and the old quarter of Buda with its cobbled, zigzagging streets descending steeply down to the Danube. Encouraged by Sàra’s prompting and the wine, I began to reminisce about a visit I had I had made there some ten years or eleven earlier. At one stage, I had travelled on a country bus that meandered along the banks of the Danube, past red-tiled farmsteads with hissing geese and creaking wooden carts laden with bales of hay drawn by handsome flaxen maned-horses. The graceful beech woods, sun-lit water-meadows and hedgerows, thick with cornflowers and harebells, have lingered in my memory to this day as something lost and irretrievably sylvan.

The journey had ended at Visegrad, a few miles south of Esztergom on a wide bend in the Danube and the site of a yearly medieval festival that featured a display of horseback archery in the grounds of a medieval castle. Wedged into the densely-packed throng of spectators, I watched as a dozen or more fierce-looking Magyar horsemen, riding at full gallop had relinquished their reins as they drew their bows and whizzed their arrows into the centre of the targets with unerring accuracy. As a demonstration of equestrian skills, it could hardly have been bettered.

“Every male Hungarian believes he was born on a horse, “Sàra laughed, “It goes back to the time of the Hussars in the wars against the Ottoman Empire.”

Ewan poured the last of the wine and I took the opportunity to ask if I could join her on one of her field trips before I left.

“Why not?” she said. “But I warn you. I start early. Six o’clock. Can you make it?”

I assured her fervently that I could and we agreed on the day after next.

It was shortly after six when Sàra collected me and the sun was just beginning to rise over the distant ramparts of the Matthews mountains. The air was deliciously cool and the light shifted imperceptibly through shades of citron, saffron and salmon pink. I clambered into her land-rover, which she had provisioned with a large flask of coffee next to a green cooler bag containing mineral water, and we drove off. Flocks of sandgrouse wheeled and dived with pin-point precision for tiny dew ponds in luggas, and vulturine guinea-fowl with brilliant cobalt-blue breast feathers scattered in front of the vehicle. An hour or so after we had set out Sarah braked and pointed in the direction of a termite mound. Seated upright on top of it was a female cheetah with her three cubs. I focussed my binoculars and her small head with the distinct black ‘tear-drop’ streak running from the corner of her eye down to her mouth swam into view. She was scanning the plain from her vantage point for both prey and possible predators, alert to every change and movement in the shifting dynamics on the savanna around her. Beside her, three cubs probably no more than four months old and still with a thick grey-yellowish ruff, called a mantle, stretching from around their necks to along their backs, romped and chased each other. Cheetahs suffer from a cripplingly high infant mortality rate with only five per cent surviving to adulthood because of predation by lions, hyenas, jackals and birds of prey. The mother needed to kill to feed her increasingly ravenous family but this could often involve long distance journeys, something she was reluctant to do.

“That’s Zsa Zsa,1” Sàra said and laughed at my predictable reaction. “I’ve been following her since she gave birth. Her cubs are still totally dependent on her for food. And, of course, because of predators she can never relax her guard for a moment.”

I asked her if hyenas would mount an attack if the mother was there.”

“It can happen. Only last week I saw Zsa Zsa confront a female hyena who was threatening her cubs. She went for it head-on, regardless of the risk. It was total parental care in action.”

“And the hyena?”

“Backed off in submission.”

We watched in silence. The three cubs gambolled around their mother and licked and nuzzled each other. Far out on the plain, small groups of impalas grazed with quick-dropping heads amidst a large herd of glossy looking Grevy’s zebra. A Somalia ostrich with grey-blue neck and legs emerged from a cluster of thorn trees with its curious bouncing gait and from behind a grove of euphorbia three reticulated giraffes with their dark chocolate polygon markings and graceful Modigliani-like necks regarded us meditatively.

Suddenly, Zsa Zsa flattened herself on the ground, every nerve and fibre of her streamlined body tuned to the presence of a male impala that had strayed from its herd. She remained motionless, assessing the distance, evaluating the expenditure of energy involved in the chase.

The impala moved closer then stopped, head raised, its nostrils quartering the air and abruptly Zsa Zsa exploded into action, her long, fluid legs effortlessly eating up the ground in pursuit of the wildly swerving and jinking gazelle. It was like watching a finely tuned racing machine. The cheetah’s streamlined and lightly boned frame, with flexible backbone and small head, can accelerate from zero to 80 k. M.h. in three seconds, faster than any sports car. Put a cheetah and a Porsche side by side on a race track and the first hundred yards would be an even-money bet.

Then, suddenly after a few hundred yards she stopped and pulled out.

I let out my breath and glanced at Sara.

“A cheetah’s sprint time at full speed is very short,” she explained. “After that their breathing rate goes up sixteen breaths per minute to nearly one hundred and sixty. Zsa Zsa realised it wasn’t going to work, so why expend energy? She knows there will be a next time.”

A mystery surrounds this charismatic creature that all but vanished at the time of the last great glacial retreat ten thousand years ago which saw a mass extinction of megafauna in Eurasia and America. In the case of the cheetah only a fraction of the population in Africa remained. The resultant severely restricted gene pool has led to a lack of genetic diversity and an inability to withstand outbreaks of infectious diseases. Disease and illness attack a weak immune system, invariably leading to death in young cubs,

The oldest by far of the big cats, the cheetah were hunting on the savanna twenty-five million years ago when mega-predators like the sabre-toothed tiger prevented the evolution of the lion and leopard until around two million years ago. Cheetah once ranged across the entire African continent, except for the Congo Basin. Today they are found in less than twenty-two percent of their historic African range, their natural habitat usurped by expanding human populations and their livestock. Less than a century ago well over one hundred and twenty thousand were to be found across the continent. Now that number has been reduced to less than ten thousand and the future of these charismatic cats is beginning to look precarious.

On the way back, I remarked on the absence of other cheetahs in the area.

“With females, it’s normal,” Sàra replied. “They raise their cubs on their own, teach them survival skills, how to kill, what to kill and what not to.” She rolled her eyes ironically.“These girls aren’t interested in sisterhood. Their cubs are what count.”

Two days later, Ewan drove me out to the airstrip. On either side of the track the landscape stretched away empty and unbounded to the horizon under the endless canvas of blue sky. It was easy to think in a setting like this that Zsa Zsa and her kin had space for Africa but I knew that Sàra was right when she had said their future hovered in the shadowlands. Ultimately, their fate would depend on finding a solution that allowed for them to coexist with people and their livestock, which is why a project like the one she was involved in was vital if the decline of this beautiful, enigmatic creature was to be arrested.

* * *

1.Zsa Zsa Gabor. Glamorous Hungarian-American actress of the 1950’s famous for her flair and style.

THE INDOMITABLE HORACE

They [animals] are so much more straightforward and honest. They have no sort of pretensions. They don’t pretend they are God. They don’t pretend they are intelligent, they don’t invent nerve gas and above all they don’t go to cocktail parties.

- Gerald Durrell

“She was found cowering and trembling in a rain ditch by the edge of the road,” Sarah Carter told me pointi

ng towards Harriet, a sleek, young serval cat that was leaping and prancing like a mini-model in a spotted coat around the legs of Pippin, one of two resident duikers, on the gently sloping green lawn of the Twala Trust Animal Sanctuary in Zimbabwe. “She was thin as a rake, her coat matted with filth and she was terrified of everything and everyone. Now look at her.”

Sarah was a youthful fortyish with dark hair, stylishly but practically cut under a soft slouch hat and smiling eyes that hinted at more than a trace of mischief. She had started the sanctuary together with her partner veterinarian Dr Vinay Ramlaul in 2011 as a non-profit organisation focusing on the rescue and rehabilitation of wild and domestic animals from all over the country. Wherever possible the rescued animals are released back into the wild but inevitably some, like the two lions Shani and Shungu, will stay here for the rest of their lives.

Twala was named after Sarah’s first caracal whom she clearly adored. “In fact, he was christened in error. My sister asked someone the Shona name for caracal which is Twana but misheard it as Twala. However, since that is the Ndebele word for ‘to raise up,’ it all worked out quite well.”

We proceeded to a large wired enclosure containing a pair of tawny-eyed eagle owlets, perched on a branch like a pair of fluffy gargoyles who regarded us meditatively, clicking their tiny beaks from time to time as though to remind us they would soon be feeling hungry. Even at that age their eyes had the faintly reproving look of an elderly spinster aunt. Owls are one of those special species that light up our imagination. They have, after all, been around for some seventy million years and as a child I bought in unreservedly to the ‘wise owl’ myth. That was long before I lived in Athens, named after the goddess Athene to whom the owl was sacred. From the sixth-century BC, Athenian coins were minted with an image of the goddess on one side and an owl on the other and it was from then that the bird became synonymous with wisdom.

It so happened, that a few months earlier I had been in Selborne, a small, rural village in Hampshire set among gently wooded hills and open meadows that can have changed little in two and a half centuries and which is famous as being the home of Gilbert White, the pioneering English naturalist and ornithologist. A country parson, born in 1720, White passed the greater part of his life writing letters containing meticulous and vivid observations on local natural history to fellow naturalists and friends. These letters, published late in his life, were the basis for his extraordinary and enduring book The Natural History of Selborne, which in the two hundred and twenty-eight years since it was first published, has never been out of print. Amongst his many admirers was the young Charles Darwin.

Somewhere East of Eden

Somewhere East of Eden